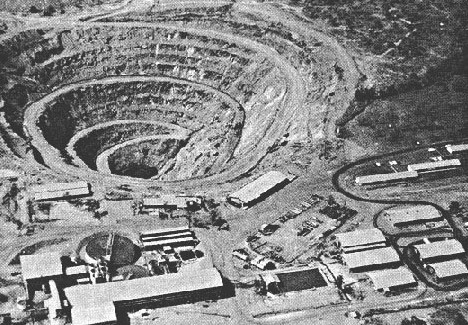

Rum Jungle, 60 km from Darwin in the Northern Territory, was once famous for its uranium mine. From 1953 to 1962, copper, lead, and silver were extracted from the 200-hectare mine site. The mine finally closed in 1971, over 50 years ago, but its fame has turned to infamy. Acid rock drainage mobilised heavy metals, and the Finniss River, into which mine waste drained, became one of the country’s most polluted waterways.

The contamination led to a significant decline in fish populations and other aquatic life in the river. Attempts at remediation have been conducted since the 1980s, but there has been no attempt to assess the possible exposure to toxic metals by aquatic organisms or humans living in the area. In fact, very little information on the pollution in the river has been provided to locals and Traditional Owners living in the area, the Kungarakan, Maranunggu, Wadjigan and Warai peoples, even though the river has traditionally been a major source of traditional foods.

I was originally intending to conduct a study of turtles in the river, but growing concerns among the community prompted me to take a closer look at the health of the Finniss River food web more generally and assess whether food obtained from the river is safe to eat. While there has been ongoing monitoring of toxic metals, there is no information on heavy metals in the food chain.

One of the metals in which I have been particularly interested is mercury. However, the specific methods and analytical techniques required to understand mercury concentrations have not been applied properly in the Finniss River monitoring. In fact, there is little information in the literature about mercury concentrations in the Northern Territory, perhaps because concentrations of mercury in Australian soil are generally low.

There is good reason to suspect mercury might be a problem despite low background levels of the metal. Mercury is often associated with gold mining, but it can also be released to the environment in small amounts during the processing of uranium and copper ores. The acidic water produced from the Rum Jungle mine’s waste rock and tailings will also have the capacity to mobilize natural mercury from surrounding rocks. There is also the possibility that improper disposal of mercury from older equipment or processing methods may have contributed to contamination.

The food web of the Finniss River I am building should help in understanding the pathways that may lead to toxic metal exposure. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes, total mercury (THg) and methylmercury analyses are part of my methods. So far, I have found that mussels, which are water filter feeders, have high concentrations of THg, and I think water could be involved in the process of mercury bioaccumulation. The popular barramundi (Lates calcarifer), which is at the top of the food chain, has also presented mercury concentration above FSANZ and WHO/FAO guidelines, and because of these, I am now testing target species for methylmercury. I am also analysing other commonly consumed aquatic species like prawns, crabs, and fish to verify if biomagnification is occurring in the river.

Quantifying mercury concentrations in the food web of the Finniss River is an important first step in determining the potential problem of mercury in NT rivers, more generally, especially in sites that may have been affected by mining activities. Currently, the Rum Jungle Mine site is flagged for further rehabilitation with ongoing monitoring undertaken by a company commissioned by the Northern Territory. In the meantime, we need to know where mercury is hidden in the food chain if the Finniss River is to continue to provide nutrition to the local community that the river has fed for generations.

Isabel Ely’s PhD project is being completed at the Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods (RIEL) at Charles Darwin University, under the supervision of Professor Stephen Garnett and Dr Larissa Schneider (ANU), Dr Carla Eisemberg (CDU), and Dr Vinuthaa Murthy (CDU). The project is supported by NT Government, AINSE and ANSTO.

Author: Isabel Ely, PhD candidate at Charles Darwin University, Larrakia Country/Darwin

Email: [email protected]

Twitter